The Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (text from OECS Regional SOMEE, p. 77)

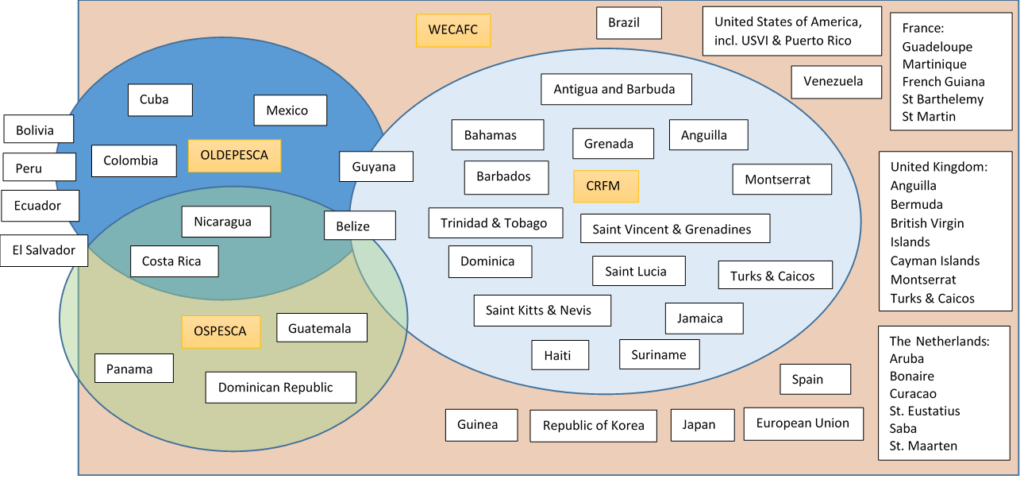

The CRFM was established in 2003 as an inter-governmental organisation with its mission being “To promote and facilitate the responsible utilisation of the region’s fisheries and other aquatic resources for the economic and social benefits of the current and future population of the region” (CRFM 2019). Membership of CRFM are Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago and the Turks and Caicos Islands. Among the many valuable contribution of CRFM to its members are the following:

- Promoting the protection and rehabilitation of fisheries habitats and the environment generally;

- Encouraging the establishment of effective mechanism for monitoring, control and surveillance of fisheries exploitation;

- Collecting and providing relevant data on fisheries resources, including sharing, pooling and information exchange;

- Seeking and mobilising financial and other resources in support of the functions of the mechanism;

- Supporting and enhancing the institutional capacity of Member States in fisheries’ areas such as policy formulation; economics and planning; registration and licensing systems; information management;

- Resource monitoring, assessment and management; education and awareness building; harvest and postharvest technologies; and

- Addressing urgent or ad hoc requests outside of the regular work program presented by Member governments.

In 2014, the members of CRFM adopted the Caribbean Community Common Fisheries Policy (CCCFP). The CCCFP is a binding treaty fostering greater harmonisation across the Caribbean in the sustainable management and development of the region’s fisheries and aquaculture resources, with particular emphasis on promoting the most efficient use of shared resources while aiming to improve food security and reduce poverty in the region. Key elements include addressing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and the integration of environmental, coastal and marine management matters into fisheries policies, safeguarding the fisheries and related ecosystems from threats and lessening impacts of climate change or natural disasters. The framework of the CCCFP has supported regional activities such as the development of policies on fisheries co-management, fisher engagement and participation, and a protocol on securing sustainable small-scale fisheries.

The Organization of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector of the Central American Isthmus

OSPESCA is part of the Central American Integration System (SICA) (see section on political and economic communities that engage in ROG) and was created in 1995 through a decision of the Central American Fisheries and Aquaculture authorities. Its objective is to coordinate the establishment, execution and monitoring of regional policies, strategies and projects related to the regulatory framework supporting the sustainable development of fishing and aquaculture activities. OSPESCA aims to encourage the development and the coordinated management of regional fisheries and aquaculture activities, helping to strengthen the Central American integration process. Its membership consists of the following countries: Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Belize and Dominican Republic.

Its functions are to:

- Promote the strategies of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Integration Policy;

- Promote and monitor the Regional Framework Treaty for Fisheries and Aquaculture;

- Coordinate inter-institutional and inter-sectorial efforts of regional scope for Central American fisheries development, with an ecosystem and interdisciplinary approach;

- Join efforts to harmonize and apply fisheries and aquaculture laws;

- Formulate and promote regional fishing and aquaculture strategies, programs, projects, agreements or conventions;

- Promote the regional organization of fisheries and aquaculture producers; and

- Coordinate an adequate and coordinated regional participation in international fishing and aquaculture forums.

Its highest authority is The Council of Ministers which is responsible for making regional policy-related decisions. The Committee of Vice Ministers, directs, guides, monitors and evaluates the execution of regional policies, programs and projects. Finally, the Commission of Directors of Fisheries and Aquaculture is the scientific and technical level of OSPESCA and is in charge of ensuring scientific and technical support for the region. The Ministers have entrusted the Vice Ministers, assisted by the Directors of Fisheries and Aquaculture, with the management, monitoring and evaluation of regional agreements (OSPESCA n.d.)

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) is an inter-governmental fishery organization responsible for the conservation of tunas and tuna-like species in the Atlantic Ocean and its adjacent seas.

Regional Coordination of RFBs

2012 MoU CRFM-OSPESCA

2020-2025 Action Plan (and declaration) p. 13-15 CLME+ actions

Interim Coordination Arrangement for Sustainable Fisheries

MoU ICM Sustainable Fisheries (CRFM, OSPESCA and WECAFC)

RFBs agree

to facilitate, support and strengthen the coordination of actions among the three RFBs to increase the sustainability of fisheries

To work towards harmonization of their respective policy and legal frameworks for fisheries

To cooperate on relevant scientific and fisheries management projects

To establish reciprocal observer arrangements

To share reports of their sessions and meetings of their subsidiary bodies and projects

Political and economic communities that engage in ROG

Many political and economic organisations work to address regional marine and coastal issues. In the Wider Caribbean, the following regional integration organizations cooperate on ocean-related policies and mechanisms: the Caribbean Community Secretariat (CARICOM), the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), and the Central American Integration System (SICA). and the Caribbean Sea Commission (CSC). The focus and approaches related to ocean policies undertaken in the region by these organizations are varied.

The Caribbean Community (text from OECS Regional SOMEE, p. 76)

The Treaty of Chaguaramas gave rise to the establishment of the CARICOM in 1973, with the goal of uniting the region through economic and political integration while also providing for human and social development and security. Currently, with a membership of twenty countries (fifteen Member States and five Associate), CARICOM represents one of the most dispersed, multi-country, political organisation in the Western Hemisphere.

The 1973 Treaty of Chaguaramas was amended in 1989 to create the Caribbean Single Market and Economy (CSME). The primary objective of the CSME is to establish a single economic space within which business and labour operate; to achieve sustained economic development based on international competitiveness, coordinate economic and foreign policies, functional cooperation and enhance trade and economic relations with third States.

There are several provisions in the Revised Treaty that seek to ensure that developments are tied to environmental consideration and specifically, management of resources in the surrounding seas (Caribbean and Atlantic). The Councils of the Community (Council on Trade and Economic Development [COTED] and Council for Human and Social Development [COHSOD]) are obliged to promote and develop policies that encourage protection and preservation of the environment, and for sustainable development, and the promotion of human and social development in the Community. Some of the other intended policies are:

- Development, management and conservation of the fisheries resources in and among the Member States on a sustainable basis;

- Effective management of the soil, air and all water resources, the exclusive economic zone and all other maritime areas under the national jurisdiction of the Member States;

- Development and expansion of air and maritime transport capabilities in the Community;

- Management of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks;

- Ongoing surveillance of their exclusive economic zones; and

- Safeguarding their marine environment from pollutants and hazardous wastes.

In 2003, CARICOM countries established CRFM (see section on RFBs above) with headquarters in Belize City, Belize. Food security for the region was undoubtedly a significant consideration in the establishment of this new RFB.

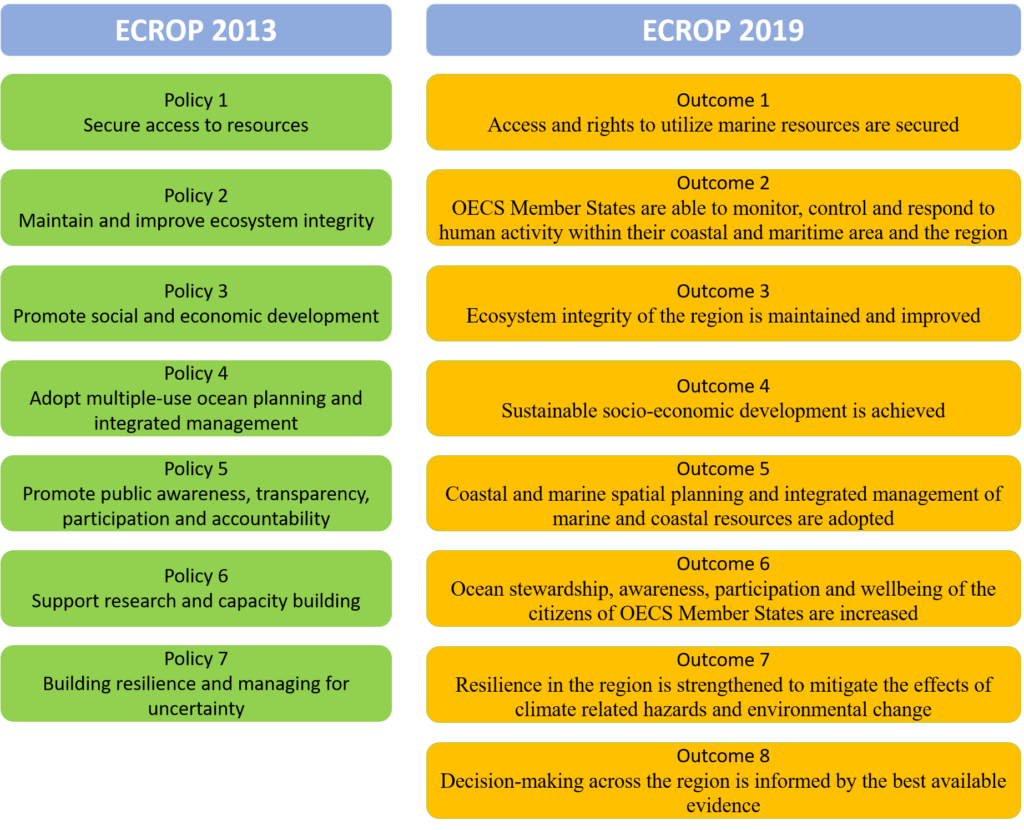

Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (text from OECS Regional SOMEE, p. 78)

The OECS is an International Inter-governmental Organisation that came into being on 18th June 1981, when seven Eastern Caribbean countries signed the Treaty of Basseterre, agreeing to cooperate with each other and promote unity and solidarity among the Members. Guided by strategic objectives including regional integration, resilience, social equity, foreign policy and high performing organisation, the OECS works with its Member States towards enhancing economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection within the Sub-Region. Various levels of support and research is facilitated by the OECS on several topics such as agriculture, biodiversity, sustainable development, climate change and ocean governance. Today, the OECS comprises twelve member islands across the Eastern Caribbean (Fig. xx): seven founding protocol members, four associate members and one non-member that has been granted observer status (OECS Commission, 2016).